(A

random Ravelry discussion triggered this post...)

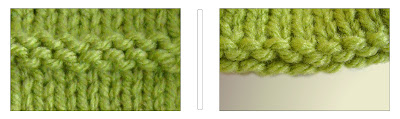

PROBLEM 1--Two different fibers which feed at different rates

When two yarns of different fibers are wound off together, they might be the same LENGTH but not work up at the same RATE. A classic example is a woolen yarn wound together onto a ball with a slippery yarn: silk, perhaps. On the ball, the two yarns look fine--they are the same length, after all. Yet, once the knitting begins, so does the trouble. The wool sticks to itself as woolly wool does, while the silk is, well, you know--silky, and does not stick to anything at all. Excess silk sags throughout the fabric, and pretty soon, a whole length of the silk yarn is sagging to leeward, between the work and the ball.

PROBLEM 2--Fibers which feed at the same rate but are wound at different rates

When two strands of yarn are wound off together but come onto the resulting ball at different tension, it causes the same problem. The two strands may feed off at the same RATE, but they are not the same LENGTH. Stated otherwise, they feed

off at the same rate but were not put

on at the same rate, making one longer than the other. Result? The shorter strand puckers, the longer strand twists and writhes and sags.

|

| Loose yarn throughout the fabric (loose lengths in pink) |

Both problems result in similar fabric, shown above. The pink lengths and dots highlight the looping and twisting and writhing of the longer/slipperier yarn (thinner in the illustration) throughout the fabric, as well as the uneven feed of the running yarn--an unevenness bound to get worse with every passing stitch. (Click on this or any picture to enlarge.)

SOLUTIONS

If winding were eliminated in the first place--if each yarn were knit each from its own ball--then each yarn would feed at its own natural rate and length, so creating an even fabric.

But what do you do when you already

have such a ball of two yarns together, either because it was wound together at a knitting shop that way, or because it came from a manufacturer that way?

You could carefully pick apart the two strands and wind each on a separate ball. Although this works, it takes forever. Before going to such lengths (har!) consider the two below options: in the right situation, these might save some hours.

Option 1--Stranding and solo stitches

Remove the excess by looping it up into a solo stitch, stranding the shorter yarn behind. The loop of this solo stitch has further to travel than the stranding running behind it, so the two yarns catch up to one another. This is the same sort of idea as stranded or Fair-Isle knitting.

|

| Shorter yarn stranded behind solo stitch of longer yarn |

On the illustration above, the thinner yarn is again the longer/slipperier one causing the trouble. At random places in the fabric--wherever an excess loop of the thinner yarn forms in the running yarn--the shorter thicker yarn has been stranded behind the thinner yarn, and the excess thinner yarn has been concentrated into a solo single-stranded knit stitch. Concentrating the excess of the longer yarn while stranding the shorter evens up the yarns, leaving the other stitches of the fabric even. The thicker yarn, stranded behind, has been colored bright green to make visible how much shorter is its path behind the concentrated excess of the pink loop.

The actual mechanics of creating the solo stitch is simple: grab a loop of excess with your right (working) needle out of the excess longer yarn sagging between the work and the ball and knit one stitch with this excess only. The shorter yarn will automatically strand behind when you knit the

following stitch out of both yarns, although you may have to separate the two with your fingers to adjust the tension.

If a single solo stitch using the excess doesn't do it, alternate this trick with ordinary 2-strand stitches along the row until the two yarns feeding in off the ball are evened up. Alternating gives better tension (and looks better) than stranding the shorter yarn behind 2 or 3 solo stitches of the longer all in one spot.

Option 2--Twisting

Remove the excess of the longer yarn--again, the thinner yarn in the illustration below--by twisting up an extra backwards loop of this yarn onto the needle. This is the same sort of idea as a

loop cast-on. However, since you don't want to actually increase your stitch count, place a pin or stitch marker at the excess loop to keep track of its location. On the next row or round, eliminate this excess loop by joining it back together with its "mother stitch," using the same sort of idea as a

k2tog.

|

| Excess yarn twisted up onto the needle |

The illustration above shows that at random places (wherever a loop of excess forms in the running yarn), the excess--colored pink--has been removed from the fabric and concentrated in one spot by twisted up into a loop and placed on the right needle. On the next round, this excess loop is knit together with its own "mother stitch." Each of two lower pink excess loops have already been knitted together with their respective mother stitches, while, the new live pink excess loop just formed will be knit together with its mother stitch (the double-stranded stitch at the arrow) on the next round.

The actual mechanics of this trick involve grabbing a loop of the excess out of the running yarn with your fingers, twisting it, placing it on the right needle and marking it.

Twist variations

The marker is shown as a safety pin, but IRL, far quicker would be several knotted loops of thin yarn kept by, each quickly caught onto the working needle when needed and constantly recycled as each excess loop is eliminated in its turn.

One easy variation to avoid having to making the stitch at all is to simply pass the twisted-up loop over the neighboring stitch to the LEFT as soon as that neighboring stitch is formed. On the downside, this uses up less excess and causes a bump, on the upside it is quick, and in many "art" yarns the bump would pass unnoticed. Passing over is pretty much the equivalent of wrapping the excess yarn around the neck of the newly formed stitch, and you could try it that way, too: passing a newly formed stitch from right needle to left needle, wrapping it with excess yarn, then returning it, wrapped, to the right needle.

A geek variation on the twisting option is to substitute an analog to the "

nearly invisible increase" (NII) for the twisting, working the NII with the (pink) excess only. The NII-analog actually gets rid of more excess in each pink stitch than the twist because each excess stitch is longer. Again, though, mark the new loop to avoid inadvertently increasing the stitch count.

Which option when?

I bought 8 cones (!!) of wool, custom-wound of three thin yarns together. Although each yarn is the same fiber, the winding machine occasionally skipped, leaving one yarn either protruding or puckering. Stranding is the better choice in this smooth yarn because twisting would have created a lump. Yet, stranding might look odd on a reversible garment, depending on the yarn and stitch.

On an "art" yarn where the manufacturer had wound two different kinds of fiber together, both options worked. In fact, there were some places where the feed was so uneven that both options were obliged to be worked at the same time--the shorter yarn stranded behind a combo of a solo-stitch PLUS twisted stitch, and this combo repeated sequentially on every alternate stitch for several stitches in a row, several times a round.

--TK

You have been reading TECHknitting blog on: "uneven yarn feed"