|

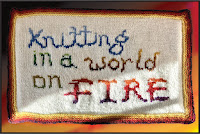

Knitting words and letters is today's topic. In a world on fire, banners have historically announced one's view on things, and, fair warning! I'm stating my political beliefs below.

Obviously, politics aren't strictly necessary: a common example of banner-knitting is putting names on Christmas stockings.

The top part of this post is technical, but you have been warned! The bottom part is, indeed, political.

What exactly is banner knitting?

Banner knitting is a constellation of tricks for knitting writing. Technically, it is a specialized form of knitting words, letters, or other thin designs, where narrow columns, curves and diagonals are set against a plain background, like words on a banner. With a plain background, there are no filler designs to carry the yarn past the end of the words, so the color knitting ends where the words do.

All the rules for color-knitting apply to banner-knitting, but additional tricks smooth the fabric and balance the appearance of different colors between the words and the background--solving a problem sometimes called "color dominance" thus making words more legible. Also, banner-knitting employs special tricks for dealing with the tremendous number of tails generated while knitting, all coming to an end nearby one another.

No longer are sayings restricted to cross stitch or embroidery. With these tricks, your words can efficiently be knitted, as well.

So, what are these tricks?Use wool

On a microscopic level wool is scaly and hairy. Two layers of wool held near one another will velcro together as the scales catch one another like barbs on a fish hook (and this can be encouraged by needle felting). Banner knitting has floats on the back, so the scales of wool help the floats and fabric surface nestle tight. Other fibers doesn't offer these advantages. Superwash wool is specifically treated to smooth the barbs, while non-wool fibers have no scales or barbs in the first place. Therefore, choose non-superwash wool for best results in banner-knitting.

Steeking

Purling back in color when knitting flat is quite the trick. Even working a front-side row, where you can see what every stitch is doing, it is challenging enough to maintain tension while wrangling 2-color knitting. Purling back on a project ups that challenge significantly. It can be done. However, ordinary mortals such as myself usually choose to make life easier by working color knitting in the round. Each cc stitch can be seen as it is applied, and background puckering becomes immediately evident. For garments (hats, sweaters) knitting in the round is no problem. For flat objects (banners, pillow tops) this means steeking. So for flat work knit in-the-round, plan to leave plenty of stitches for the steek itself when laying out your design.Even tension

A basic requirement is to knit the contrast color (cc) stitches of each letter to the same tension as the background so there's no puckering. How to knit evenly in color is a whole topic in itself and one to master before starting on banner knitting: links to some tricks and hints. Yet, while knitting evenly is the basis for success, there is more.

Relative Yarn weight

Contrast color (cc) yarn for words should be of at least the same weight as the main color (mc) of the background. But better is a cc yarn in a slightly heavier weight. You may have come across yarns described as being in the same weight category, yet one is thinner than the other. You would use the heavier for the words and the thinner for the background.

|

| The white yarn (Cascade 220) in noticeably thinner than the red (Pattons Classic). Both yarns are technically capable of being knit at 5 st/in. Yet in these two particular balls, the weight difference means cc red words (heavier yarn) on an mc white background (thinner yarn) would more legible than white words on red. |

Splitting yarn

Luckily, comparative anatomy among the yarn balls is not actually required to achieve this subtle weight difference. Instead, you can actually thicken and fluff up a cc yarn, even if it the same weight as the background yarn. This is done by splitting yarn into its component plies. When split plies are rejoined, the rejoined yarn is fluffier than before splitting. The letters are then knit with the splits both held together as one yarn, while the background is knit with unspilt yarn.

An example of how this works. The banner above is knit in 4-ply Norwegian long-staple DK wool (Peer Gynt and some old balls of Dale Garn Heilo). The light background is knit with yarn as it comes from the ball. But, the colorful letters are knit from yarn split and then rejoined. Specifically, the letter-yarn was divided into two 2-ply splits. Then, the two splits were held together and knit simultaneously, as if they were one yarn. (Lower, there is a photo showing this.)

Two splits held together are fluffier than an unspilt yarn of the same weight, assuring that single cc stitches don't sink into the background to get lost. Yet, as the split yarn passes through the background fabric on its way to becoming a float across the back, the splits compress together to their original weight. In this way, splitting yields a fluffier yarn on the surface, yet doesn't affect tension or distort the fabric it passes through.

Another advantage: splitting allows creating more colors by mixing. If you enlarge the banner-photo at the top of this post, every word in this banner has at least a few rows of color mixes. Another example from a different banner: in this letter "B," there are lots of color mixes to create an ombré effect.

A further advantage: as sketched below, splitting lets you loop together shorter lengths of yarn without having to splice them. Even if one ends up on the fabric surface, a loop-joint is pretty near invisible, so this trick lets you easily piece two shorter strands into one longer.

|

| looping shorter splits together instead of splicing |

Direction of knitting: V's up or down

For banner knitting, you can graph out words using free-handed letters, or use alphabet samplers. Problem is, graphs and samplers are laid out in little squares. Yet, as you know, stockinette stitches are little "v's," like downwards ▼ arrows. Sometimes, letters look better if the v's point up ▲ instead. Consider flipping your chart 180 degrees so the letters are upside down on the graph paper, then knitting words from top down. Below are some letters knit this way, a "Y," and another look at the "B" from above.

In swatching, I liked how the upwards v's made a more graceful line on descending tails, and added little spiked helmets like "pickelhaube" as decorations above the line.

Knitting smooth and even letters

Years of experimenting with narrow columns and diagonals yield two rules I rigidly follow: "lifting" and "continuous coverage."

Lifting over avoids "color dominance." First rule is, each yarn to be knit must be brought OVER the yarn already knit. When you go to knit a cc stitch, that yarn is lifted over the previous background stitch. Similarly, the yarn for a background stitch is lifted over the previous cc stitch. In this way, every stitch change starts off slightly raised on its leading edge, where the new yarn enters the fabric front face over the bump of the yarn not in use.

This is another way of saying that "color dominance" has no place in banner-knitting: by lifting each yarn over the previous, both yarns are equally dominant. This consistency prevents contrast stitches sinking into the background or vice versa.

Lifting over is tedious. For one thing, you cannot knit "two handed," or even with a "fingerhut" yarn guide, as you might work ordinary color-knitting. Instead, you must continuously drop and pick up the new yarn.

In ordinary two-color knitting, lifting causes a further problem as well: it makes an awful tangle of the yarn as each pick-up winds each yarn further around the other. Yet, this turns out not be be much of a problem in banner knitting.

Recall that there are no designs past where the writing ends. This means you need knit with strands only long enough to span across the words + tails: fairly short strands, really. Therefore, the easiest way is to cut each cc strand to approximately the correct length before the knitting of that row starts--experimentation will soon show you the length to cut. Now the cc is a loose strand, rather than being knit from a ball or bobbin. A loose strand untangles by simply pulling it out of the resulting bird's nest. Frequently pulling loose the cc strand makes lifting much easier that it first seems it would be. Still tedious, but not awful.

Continuous coverage with cc yarn across the fabric back

A second rule for successfully knitting narrow columns is to apply the yarn in continuous rows across the fabric, spanning the width of the writing. This is easiest to see from this back view, where the floats march away in even bands across the back.

|

| ...floats march away in even bands across the back. |

It may be tempting to break the rule of continuous coverage to knit with some strand of yarn which happens to be dangling off the fabric-back in just the right place. And truly, for something like dotting an "i'" (red circle) that would make sense. It may be tempting to double the yarn back and knit with its tail. And, perhaps, for the descending stem of a letter like "y" that would make sense too. But overall, the way to knit smooth letters is when the stitches in each row are applied with their own strands of yarn all the way along, all in the same direction, knit sequentially and lifted over: smooth bands of cc yarn spanning the fabric back continuously from one end of the writing to the other.

Parking

Using short-ish loose strands in continuous coverage makes for smooth letters, but the price is a lot of ends. Letting all those ends dangle on the fabric back during the knitting process makes an awful mess, unpleasant to knit. Therefore, a good trick is to temporarily park them on the fabric surface by holding them in a "parking column" to the fabric front.

Below you see ends parked on the fabric surface as a banner is being knit. Some of the ends have already been worked in, (the words "on" and "FIRE,") while some remain on the surface awaiting their turn. For example, the tail ends of the blue strands used to knit the word "knitting" are parked several columns before and after the letters of that word, and where they rise to the surface, that is the parking column. As is evident, to knit the lower loop of the "g" with continuous coverage meant using quite short strands, as also for the upper parts of the "t's." Similarly, continuous coverage for the tops of the letters "l" and "d" in the word "world" yields short strands parked on the surface three columns from where those letter-tops project above the lower-laying letters.

|

| The many ends controlled by being drawn to the surface in "parking columns." |

In this closeup, the fabric is rotated clockwise (left side up) showing how parking results in a neat back, with the tails kept out of the way until it is time to fasten them down.

It's not just the fabric back that's neater, either. Because the tails are parked on the surface, it's easy to adjust the tension of stitches in first and last columns by tugging gently on the corresponding tail where it emerges. As you knit, it pays to periodically go back and adjust stitches which are obviously working loose. This begins the process of settling the stitches into their proper places before they have a chance to kink into a larger, looser shape.

As to the how-to, there are two ways to park a cc strand at the beginning of a row.

- When you first come to the parking-column, stop and insert the cc yarn, then knit the last few mc stitches, then commence with the cc.

- Alternatively, let the cc tail dangle initially, then draw the tail to the surface in the parking-column after you've anchored the yarn by knitting a few cc stitches.

Either way, you have to stop and park the cc strand between stitches of the mc background in the parking column, but with after-pulling you'll also need a crochet- or latch-hook.

Tails at row-end offer the same options.

- Park as you pass the ending parking-column.

- Alternatively, let the cc strand dangle temporarily, knit in background color a for a few stitches past the parking-column, then afterwards park the dangling cc end on the fabric surface by using a crochet hook to draw it through the parking-column.

One advantage to after-pulling is the opportunity to divert tails to a different row than the one in which they were knit, thus parking them out of the way of other tails ending nearby.

Floats and float-tricks

Ends are not the only loose strands of yarn to deal with in banner knitting. There are also floats, and these can get quite long between words, or even between letters which face away from one another. There are two main ways to deal with floats, either as-you-go, or afterwards in the finishing process.

As-you go float control: Ladderback jacquard, STUART technique

Some knitters choose to twist together the main yarn and the cc yarn every few stitches along the length of the float. This trick certainly holds down the floats, but ups the probability of color-blips on the surface. The greater the contrast between the main and cc yarns, the more likely blips are to show. For this reason, interrupting a float half-way to wind it around the mc is not my favorite way to control long floats.

If you prefer to deal with long floats as-you-go, a better option is ladderback jacquard, and there are many ways of working this. My own take on ladderback is called STUART, which stands for "Slip Then Unhook And Rehook Twice." Because there is a whole post about this trick, I won't repeat all that here, but just show an example from the "world on fire" banner--here is that banner again for reference.

This ladderback is worked on the back of the letter "F" of the word "FIRE," bottom line of the banner. Some floats in this spot reach as far as 18 stitches.

Controlling floats afterwards

One defining feature of banner-knitting is the tremendous number of ends which have to be worked in. This means there is a great deal of finishing to do. Because there is so much finishing, an alternative to as-you-go float control is to simply knit the floats loose and long, then deal with them, too, as part of the finishing process.

Tacking

A good trick for controlling long floats in the finishing process is called "tacking." I have already written about tacking, as well as the truly invisible variant of tacking, worked using sewing thread. Because the thread variation is, literally, invisible on the fabric front, I can only show the results on the fabric back.

|

| Tacking with sewing thread--long floats between "I" and "R" |

.Two-part Floats

Another trick with floats is to knot and loop together ends. I call this trick "two-part floats," because it turns two sets of ends into one set of floats. In the "fire" banner, I used this where words of two different colors come together, such as between the phrases "in a" (green) and the word "world" (brown-gold). I could have worked these strands in as parked ends. However, these words are very close, so there would be many ends to deal with over a short a stretch of background fabric. Therefore, I thought knotting the ends into two-part floats the better option.

It is a maxim of knitting that knots in garments are rarely a good choice because they create hard bumps, they want to come loose, and they want to work their way to the fabric surface. So, I would mostly save this trick for situations where the fabric back receives no wear: banners and cushion tops.

Here is a schematic showing the idea.

|

| Concept sketch, two-part floats |

The graph represents the letters "a" and "w." Recall that the banner was knit with splits. This means knotting the tails together makes a loop. Accordingly, I knotted together each brown or gold tail from the letter "w." I then looped the green yarn through the brown/gold loop to knit the stitches of the green letter "a." In this case, the knitting was right-side up (downward pointing v's) so that the letters were worked <-- right to left. Of course, this sketch is only a conceptualization. The loops are on the fabric back while the letters are knit on the fabric front.

As you see, the two words are not horizontally aligned, meaning, each brown/gold loop was knotted but left on the fabric back to wait for the appropriate round, when the green yarn would be looped through, then knit.*

Here is a closeup of the actual two-part floats on the back. Because this photo shows the fabric flipped over, the floats now appear to be going the other way.

|

| Two-part floats IRL |

I have to admit that even on a banner back, where there is no wear, knots in yarn want to undo. However, these particular knots cannot follow their inclination to pop open because I felted them shut. Using a single dry-felting needle, I stabbed each knot several times from various angles until the knots gave up trying and laid quietly. This also let me cut the knot-tails shorter than I otherwise could have. Read more about needle felting in the immediately preceding post.

As a practical matter, two-part floats cannot really be secured by ladderback methods, but must be afterwards fastened.

Afterward controlling long floats by needle felting

Another option for afterward controlling long floats, plain or two-part, is needle-felting them in place during the finishing process (video).

Touching up letters

In the previous post on needle felting, I also showed using a single felting needle to delicately touch up letter-stitches which don't connect on the diagonal. This is called surface felting, and here is an example of improving a knit letter "o" using this technique.

A white stitch arm (leftmost panel, red arrows) intervenes between two dark stitches at the top right. By inserting a single felting needle across the gap (middle panel, blue arrows) the gap is covered over by a few wisps of dark yarn. Now the diagonal is continuous (rightmost panel). More details about surface felting.

* * *

OK! Woolen yarns have been selected. The letters have been charted and direction of the v's determined. Sufficient stitches have been left for the steek. The yarn for the letters has been split and rejoined. The letters have been legibly knit via lifting, with continuous coverage of cc strands along the fabric back. The many ends are either parked or worked into two-part floats. The ordinary floats have been fastened down as-you-go (ladderback) or await being fastened in the finishing process (tacking or needle-felting). The letters have been touched up to read in smooth diagonals. What now?

This post is long enough already. As I hinted above, I'm putting off to the next post, the many ways to tidy up the back and work in ALL THOSE ENDS parked on the fabric front.

I will instead end this post by showing two further banners I've knit. Fair warning! In classic banner tradition, the subject is politics.

.Politics

If you believe in your heart that everyone must get along with no free help from you, you know in your heart that you need no free help from me.

I like to think that, through the strength of their convictions, such readers have avoided TECHknitting these past nine years. However, if you're a Trump voter somehow still reading here, I address you directly.

By your vote...

Knitting for a world on fire

Many wrote to ask whether TECHknitting is going to shut down again like last time Trump was president. The answer is no. Sometimes I wonder who's out there reading, but wow! the emails and dm's on this subject have been more than on any single point of knitting technique, ever. I shall do as you ask, and not shut down this time. Disillusioned? Fuming? In disbelief? You are. I am. Yes. But this time, I plan to stay and hope you will too.

Meanwhile, knit a banner. Hang it at the county fair. Enter it in a knitting competition. Wear it on your chest. Call it knitting for a world on fire.

And, if any Trump fans got down this far, here is my final banner. I assume you are setting up to bid me farewell, and I bid you the same. For the second time inside a decade, I say....

* * *

For the rest, lovely readers, I will see you next post, where the subject is working in all the many ends resulting from banner knitting. A third post relevant to banner knitting shows a steek-and-finishing method very well suited to sayings and wall hangings--it is called "Double fold-back steek."

--TK

* The green was knit in splits also, and where those splits were multi-hued, the strand was fabricated by felting (spit-splicing) the two greens together at the apex of the loop. The overlapped part of the splice (multi-hued) mostly stayed parked on the fabric back. The brown/gold strands could not be spit-spliced into a loop because there's simply not enough room on such short ends to work that kind of splice, hence the necessity for the knot.

* * *