8 illustrations Click any illustration to enlarge

A buttonhole, a pocket opening, the bottom of a neck opening: these are all examples of binding off in the middle of a fabric. This sort of binding off often looks very sloppy indeed, both where it starts (at the right edge of the bind off) as well as where it ends (at the left edge of the bind off)

Today's post concerns the starting part of the bind off--the right edge. The next post will be about the ending part of the bind off--at the left edge.

Let's say that our pattern requires us to bind off several stitches in the middle of our fabric, using the chain bind off.

(Click here for further information on the basics of the chain bind off). First we'll look at the traditional method, and then the improved method.

The traditional method

Illustration 1, below: Many books do not have any preparation step for binding off in the middle of the fabric. Rather, you are instructed to simply begin with an ordinary chain bind off as illustrated below: the last stitch of the fabric will be the

teal stitch, while the first stitch bound off will be the

purple stitch, which is being drawn over the

green stitch. As you can see, the

purple stitch is connected to the

teal stitch by the little

red tail, and we'll talk more about that little tail in illustrations 3 and 4, below.

Illustration 2, below: According to the traditional method, you are then instructed to continue the bind off as for an ordinary bind off, so the situation looks like this:

Illustration 3, below: As you can see, using the traditional method, the last fabric stitch (

teal) and the first bind off stitch (

purple) are connected by nothing other than a single strand--the tail yarn which connects the

teal stitch to the

purple stitch. This little tail (

red) is going to form the bottom right corner of the bind off.

Sadly, over time, the result is going to be an

ugly and

weak gap. As the teal stitch and the purple stitch stretch ever further apart they will stretch and expose that single red tail. In close-up, the situation is going to look like this:

Photograph 4, below: Here it is in real life, in all-purple yarn. The red arrow is pointing to the stretched-out single tail in the lower right corner of the bind off.

The improved method

To get rid of this ugly, weak gap, let's try this trick: instead of starting the bind off with the

purple stitch, we'll do a little sleight-of-hand with the

teal stitch. Remember that what we want to do is to improve the connection between the last fabric stitch and the first bind off stitch. As it turns out, when we use a kfb increase (knit front, back), the two daughter stitches which result are hooked together by a veritable spider's web of yarn. So, let's turn that fact to our advantage.

(For illustrated instructions on how to work a kfb, click here.)We'll use a kfb increase and force the teal stitch to do double duty by turning it into the last fabric stitch AND the first bind off stitch. In this manner, we'll be able to position that strong connection between the two stitches just at the weak corner. In other words, in this improved version of the chain bind off, we are going to use the kfb increase to create

TWO teal stitches--one to lay in the fabric, and one BONUS stitch, with the strong connection between these two stitches positioned at the weak corner.

Illustration 5, below: Under this new improved method, when we come to knit the teal stitch, we will work it as a kfb into its underlying foundation stitch. As you can see from the illustration below, this results in TWO

teal daughter stitches. The

kf part of the foundation stitch lays under the first teal stitch, and this part of the foundation stitch is

brown, whereas the

kb part of the foundation stitch lies under the second teal stitch, and this part of the foundation stitch is

orange.

Illustration 5, above, shows the very real benefit of using the kfb increase. You see, due to the kfb increase, the two teal stitches are not merely connected by

one single tail like ordinary stitches--no! Rather, they are connected by

three strands of yarn: the two

orange strands in the twisted portion--the kb portion--of the foundation stitch, as well as the one-strand-tail (

red) between the two teal stitches themselves, making three strands altogether. So, instead of the single red tail from illustration 3, by the traditional method, we have three strands--two orange and one red--to fortify our corner by this kfb trick. (There is a close-up of this in illustrations 7 and 8, further down this post.)

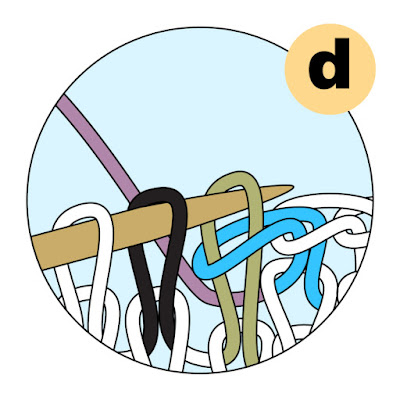

Per illustration 6, below, we'll begin our improved bind off by drawing the second

teal stitch--the bonus stitch which we made--over the

purple stitch, then the

purple stitch over the green, and so on.

Here is something important to remember about the teal bonus stitch: We do not COUNT it as a bound off stitch. Remember: the second teal stitch is an EXTRA stitch which we've created with only one purpose in mind: to put more yarn into that weak right corner of the bind off. Because we created it as an extra stitch, a bonus stitch, we do not count it when we get rid of it again.

In other words, the second teal bonus stitch flashes into existence for only a brief moment: we create it, then draw it over the first stitch to be bound off, and then the bonus stitch is gone forever. It leaves behind only a stronger corner, but it never alters our stitch count. It is only when we draw the

purple stitch over the next (

green) stitch that we start counting our bound off stitches--the purple stitch, NOT the teal bonus stitch is the FIRST bound off stitch.

Below, illustration 7, is a close up of what the improved corner looks like once we've add the

teal kfb bonus stitch. As you can see, the corner which had only a single, weak red tail by the traditional method now has a sturdy spider's web of yarn fortifying the corner in this improved version. Instead of one strand of yarn, three strands of yarn lie there now--the two strands at the top of the bonus stitch's foundation stitch (

orange) as well as the bonus stitch's own tail (illustrated in

red). This construction will last far longer than the unimproved traditional corner of illustrations 3 and 4.

Photograph 8, below: here is what the kfb looks like at the start of a bind off, in real life, in all-purple yarn. Although you can see the extra yarn in illustrations 5, 6 and 7, yet in an actual photograph (8) you can see that all these extra fortifying loops are actually hidden away, and all you see is the front of the bonus stitch. In other words, even though you've packed that formerly weak corner with lots of yarny fortification, the front presents a nice, even appearance instead of the the loose, sloppy and weak single strand in illustration 3 and photograph 4, above.

I think you will find that over time, this little trick of fortifying the right corner of a bind off by starting the bind off with a kfb will pay off in sturdier buttonholes, more robust pocket openings, and easier to pick-up-through neck openings.

One last thing--are you worried that adding an extra stitch to the corner will make the opening too large? In my experience, that won't happen. In fact, the tight twist introduced by the kfb will keep the starting (right) edge of the bind off tighter than by the original method, because you won't have a stretched-out mess in the corner there.

This post is part of a series. The others in this series are:

Ordinary chain bind off, part 1: binding off along a straight edgePart 2b: binding off in the middle of a fabric--ending the bind offPart 3: binding off circular knits. --TECHknitter

(You have been reading TECHknitting on: "bind off (cast off) in the middle of a fabric.")

1: Make several lengths of I-cord. The photo to the right shows 2 tassels, each made from 2 double-length cords and folded over.

1: Make several lengths of I-cord. The photo to the right shows 2 tassels, each made from 2 double-length cords and folded over. 4. For shorter tassels, a simple wind at the top to hide the tacking is all that is required, as the shorter cords look well sticking out in different directions.

4. For shorter tassels, a simple wind at the top to hide the tacking is all that is required, as the shorter cords look well sticking out in different directions.