|

| the heart of the matter |

"Cables look hard," beginning knitters say, and "what is a cable, anyhow?"

Gorgeous and complicated-looking, yet the concept is simple. Leave the paraphernalia and procedures aside for now. Start at the heart of the matter.

The heart of a cable is its cross-over, and that cross-over is nothing more and nothing less than stitches switching order along the row.

Suppose six stitches are on a needle. Labeled 1-6, they'd appear in this order as you knit (remember, per the arrow, knitting generally proceeds right to left).

6-5-4-3-2-1

<--------------<

After you've made these stitches switch places (and never mind how, for the moment) the new order would look like this:

3-2-1-6-5-4

<---------------<

The group of stitches in pink-bold and the group of stitches in green-italic have switched position. The green-italic group used to come first, but now comes last. Similarly, the pink-bold stitches used to come last but come first. The direction of the knitting (arrow) hasn't changed: that remains from right to left. What's changed is the order of the groupings.

Look closer. WITHIN each group, the stitch order hasn't changed. The 1-2-3 group still goes 1-2-3 after the switch, and the 4-5-6 group retains its internal order as well. In the end, our six stitches have been divided into two groups of three, each group retaining its original internal order, but the two groups have switched places. And that's your first cable knit! (Well, conceptually, anyway.)

Here it is again, in stitches, rather than numbers. Remembering that the <---direction of knitting is right to left, here are the six stitches labeled by number.

Now let's cross them. The 4-5-6 group which used to come last now comes first. The 1-2-3 group which used to come first now comes last. The exact spot where the two groups switch places is the cross-over, marked with red arrows.

(Preview--we'll see this illustration again in variation because there's something else happening where those arrows are. More below.)

As to knits and purls, here's what to notice:

- As seen from the front fabric face, all six cable stitches are smooth stockinette stitches.

- The opposite of a knit is purl and the opposite of a purl is a knit, so if you've knitting flat (side-to-side) then when you flip the fabric over so the back fabric face is towards you, the cables would appear as purl stitches. A corollary is that ordinary cable fabrics are not reversible.

|

| the cable express |

Now leaving the realm of theory. Next stop on this train: knitting a cable.

A first cable

Materials:

Here's what you'll need to make a cable by a very simple and intuitive way. (The "real way" used by most knitters is at the end of this post, but we'll start with this simple method.)

- scrap yarn

- needles in the right size for the yarn

- something capable of holding 3 knit stitches for a few moments so they don't run out and don't get out of order, something like an unbent paper clip, or a bobby pin (or a safety pin or a piece of spaghetti broken off short, or a piece of scotch tape, or twisty-tie bent into a U shape, or really any darn thing you can think of.)

|

| cable crossing gizmos |

Procedure

The goal is a 6-stitch cable, as in the illustrations. But we'll cast on 12 stitches, allowing for a 3-stitch border on each side for ease of handling. Onto this 12-stitch cast-on, knit a few rows of stockinette. End with a wrong-side row, so that the next row about to be worked is the smooth front knit side of the stockinette fabric. Knit 3 stitches for the border, and you're in position. The cable will be worked on the next six stitches currently parked on your left needle.

- Here comes the fun part. With your unbent paper clip (or bobby pin or tape, or whatever) catch the next three stitches as shown below. This first group of green stitches (1-2-3) will form one-half of the finished cable.

- Let the paper clip fall to the front of the work (towards you) making sure the three green stitches stay aboard. These stitches will form one half of the cable.

- Now, slip the next three pink stitches (group 4-5-6) from the left needle onto the right needle, one stitch at a time, preserving both their order and orientation (right stitch-arm forward). This group will eventually form the other half of the finished cable.

- Next, replace the first group of green stitches (1-2-3) from the paper clip onto the left needle. Again, stitch-orientation should remain right-arm-forward after the transfer.

- Last, replace onto the left needle, the second group of pink stitches (4-5-6) previously slipped onto the right needle, once again preserving order and orientation.

|

|

- Counting from the tip of your left needle, the pink 4-5-6 group will be first, though it will be crowded and squeezed together by the second group (green 1-2-3) leftwards on the needle.

- Next, knit across the top of all these stitches in their new order.

- Lastly, finish the row by knitting the three border stitches remaining on the needle. Ta da--a first real-life cable cross.

|

A row knit into the top of the cable cross.

Note: border stitches are not shown |

When the row is finished, turn the work, purl the back, turn the work again, knit the front. Now let's look at this scrap as it looks in actual knitting. The six stitches are highlighted in thin red stripes. The cable cross is at the red arrows.

If you poke around with your fingers, you'll notice there's a sort of a hole on either side of the cable cross. As previewed earlier, here's that illustration from above for comparison, and you'll see that the holes, just where the arrows point, are due to the cross itself. Such holes are normal, a structural artifact of the cable cross.

If you think about it, the stitches of the crossed row aren't connected to their directly neighboring stitches any more, but have been yanked out of order by the cross. It is true that the very next row--the one knitted into the switched stitches--re-establishes the connection between every stitch and its neighbor, all the way down the row, but that only closes the hole, rather than eliminating it. On the yanked row itself (the row of the cross-over) the loss of neighborly connection means there are unavoidably holes on both sides.

So, yes there are holes. But no, you didn't do anything wrong. It's the nature of the operation.

The wider the cable (more stitches) and/or the chunkier the yarn, the bigger the hole. Yet however significant those holes may come to seem to you as the knitter, the reality is no one else will ever notice.

Refinements

Borders / background stitches: the scrap we knit doesn't quite look like a classic cable, because the edges of the cable and the borders all merge together. If the borders were worked in purl stitches, the edges of the cable would be much easier to see: a continuous knit column on a purl background stands out clearly.

|

| purl-bordered cable (left); unbordered cable (right) |

Here's that same same 6-stitch front cross cable. However this time, it's knitted side-by-side with the same kind of cable on a purl background. By working the border-stitches in purl, the left cable looks more defined.

Left and right front crosses: In cabling, there are only two ways the cable can "lean" or slant: left or right. Therefore, cables are classified as left or right front crosses.

Note that in both crosses the stitches are in the same order, so what dictates the lean? In the sample scrap we knitted, the green 1-2-3 stitches on their paperclip holder were dropped to the front of the work when the pink 4-5-6 stitches were slipped to the right needle. After all the stitches were re-arranged and knitted, the green 1-2-3 group formed an arm of stitches crossed over on top, while the pink 4-5-6 group formed a cable-arm which squeezed behind.

With the green-stitch arm on top, the cable appears to rise UP to the LEFT (the top arm of the cable slants upwards and to the left). For this reason, this type of cable are often called a left front twist, or a left front cross, sometimes abbreviated "LFC".

Geek-note: a cable which slants UP to the LEFT can just as well be said to slant DOWN to the RIGHT. However, the naming convention has evolved to describe which direction the UPWARD slant points. If confused, think "upwards and onwards" as your motto. (An excellent motto for all kinds of knitting, really.)

Now...what if you had dropped those green stitches on their paperclip to the back of the work in the re-arranging process? Well, the green stitches would still be drawn upwards and to the left in the re-arranging process BUT that green arm would now be at the back, hiding. Instead, on top would be the arm composed of the pink (4-5-6) stitches, drawn UP and to the RIGHT. With the right-leaning pink arm forward, the entire cable appears to slant upwards to the right. Therefore, such cables are often called a right front twist, or a right front cross, sometimes abbreviated "RFC."

Below, a graphic summary.

|

Left and right cables and their method of construction

First group (green sts) placed on holder, holder dropped to front = left front cross

-->green stitches wind up in front<--

First group placed on holder, then holder dropped to back = right front cross

-->pink stitches wind up in front<-- |

The take-away here is that once crossed, the first group of stitches in any cable (green) always slant upwards to the left, and the second group of stitches in any cable (pink) always slant upwards to the right. The apparent direction of the cable cross is determined by which arm is on top, and which arm is on top depends on which way the first group was dropped when on the holder.

---> Drop to front, left cross. Drop to back, right cross <---

Repeats and direction: Cables get their characteristic look by repeating at certain intervals. So, on the six-stitch-wide cable we've been knitting, the cross would typically repeat every 6 or 8 rows. Further, cables typically cross in the same direction each time. If you think about it, you're actually knitting •two side-by-side stitch-columns (the arms) •where these two arms spiral around one another in the same direction (the cross) •at the same frequency (the same number of rows between the crosses). It's like two snakes intertwining.

Shortcuts to re-arranging the stitches a.k.a the "real way" to knit cables.

As promised, the "real"way to knit cables. This method shortcuts slipping and re-arranging stitches on the left needle before knitting.

So far, we've been making cables like this:

- step 1: slip green stitches 1-2-3 onto holder, drop to front (left cross) or back (right cross)

- step 2: slip pink stitches 4-5-6 from left to right needle

- step 3: return green stitches 1-2-3 to left needle from holder

- step 4: return pink stitches 4-5-6 from right needle to left

- step 5: stitches are now rearranged into a cable cross, and parked on the left needle. Complete by knitting all stitches.

Step 4 is now going to be eliminated, and made part of step 2.

New procedure ("real way")

- step 1: slip green stitches 1-2-3 onto holder, drop to front (left cross) or back (right cross)

- step 2: KNIT pink stitches 4-5-6, one half of cable cross completed

- step 3: return green stitches 1-2-3 to left needle

old step 4: eliminated because pink stitches 4-5-6 are already (knitted!) on the right needle.- new step 4: knit green stitches 1-2-3, second half of cable cross completed.

Cable needles

Cable needles are the original way to cable. By using a cable needle, it is possible to further streamline cable knitting.

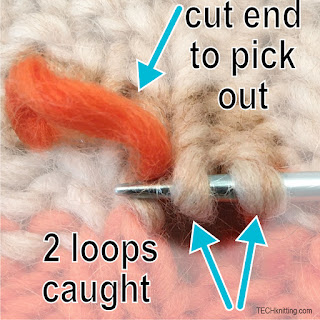

Old-style cable needles were short double-pointed needles. These easily fell out of the work. Newer style cable needles feature a dip to better hold the stitches. By using cable needles, the above procedure collapses down to only three steps.

- step 1: slip green stitches 1-2-3 onto CABLE NEEDLE, drop to front (left cross) or back (right cross)

- step 2: knit pink stitches 4-5-6, one half of cable cross completed

- step 3: RATHER THAN returning green stitches 1-2-3 to left needle, INSTEAD, knit them directly off the cable needle, second half of cable-cross completed.

Using a cable needle eliminates a step, but has certain drawbacks. Not only does it have more of a chance at falling than do most holders, but you have to switch your grip from the left needle to the cable needle to work the second half of the cable cross, then switch back again to the left needle to knit further. For these reasons, I find it slower, and do not cable this way. Yet use makes master, and you may find it faster. This traditional method has been time-tested and is certainly worth a try.

J-hook

A J-hook cable needle is not to be confused with a size-J (6 mm) crochet hook. They're both called "J-hooks" but are different tools.

|

| J-hook for cable knitting. Not to be confused with a size-J (6 mm) crochet hook |

Cable J-hooks are made of anodized aluminum or plastic and slide easily. They're a sort of hybrid item. They hold that first group of stitches as well as a paper clip or a bobby-pin, but you can knit the stitches off the long end as you would with a cable needle, if you're inclined to try that method. The only disadvantage I find is never having one at hand. By contrast, a box of paperclips or a card of bobby pins will last a long time, and no crying when one disappears.

Still another shortcut

There is one final shortcut worth mentioning, and that is "cabling without a needle." With this trick, the group of stitches which would normally be transferred to a paper clip or other holder are instead pinched in the hand of the knitter while the other group is being knit. I've not found this method faster for myself, but it certainly is clever, many knitters prefer it, and it's an excellent trick to know for a cabling emergency. Here are links to

two different blogs with instructions.

* * *

Before we leave the subject of cables, it would be a mistake to think all cables are six stitches wide. There are whole BOOKS of different cables, a quick internet image search reveals hundreds, and stitch dictionaries usually have a cable chapter as well.

Another mistake would be to think there are hard-and-fast rules. Every convention mentioned here can be broken. Cables need not have two arms--they can have three, four or more. Cables need not always be made in stockinette--and even if one arm is stockinette, the other(s) need not be. Cable arms need not be of the same stitch court--one arm can have more stitches than the other(s). Cables need not have a border or background, and if they do have a border, it need not be purl stitches. Cables need not repeat at regular intervals. Cables arms need not spiral around one another like snakes, but can wave back and forth like seaweed, keeping the same arm always on top. Further, cables are not always confined to the same set columns of stitches, but can "travel."

The one thing which cables share, however, is the "cross." The cross is the heart of the cable, and what this post has been about.

* * *

Til then, good knitting! --TK kn

PS: This blog is not about my life, but if you want to know where I have been, a family member has been ill.