includes 17 illustrations

Ok, I gotta say it: those were a lot of comments to the last post--the one about the possibility of including some sewing techniques. Many thanks to all who responded, and to all who will respond. The drawing for the prize--the $20 gift certificate to Knitpicks--will be on TECHknitting's blogiversery post (Nov 5, 2007). In the mean time, it's back to mundane nuts and bolts stuff about knitting--today's post is about MORE left leaning decreases.

The current series on left-leaning decreases is the result of a lot of experimentation over a lot of (pre-internet) years. At different times, different left leaning decreases were my favorites, but now I have settled on two:

the SYTK and the

Crochet Hook Method (CHM), each of which previously starred in a post of its own. However, that doesn't mean that some of the other left-leaning decreases with which I flirted weren't handsome creatures, too. I've picked the runners up below. One of these, runner up #2, is a specialty decrease you might want to remember for those situations where you HAVE to make a left leaning (as seen from the front) decrease by working from the back (purl) side of the knitted fabric.

Before we plunge in, I must warn you: this is one of the geekiest (and longest) TECHknitting posts yet. If deep-seated geekishness is not in your nature, you might want to

flee read a different blog for today...

If you're still game, here we go with 5 more left leaning deceases. Each one of these, IMHO, is an improvement on ssk and psso, but some are better than others. I've arranged these in reverse order according to my own scale of desirability (yours may vary). Runners up number 5 and 4 I find to be barely an improvement over ssk, while runner number 1, discussed last, is the one I'd go with if SYTK and the CHM suddenly fell off the face of the earth.

* * *

RUNNER UP DECREASE #5:

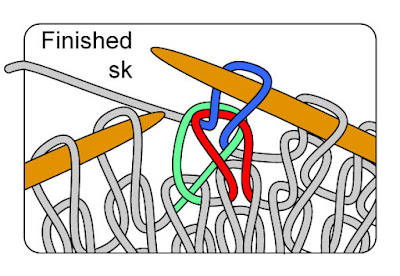

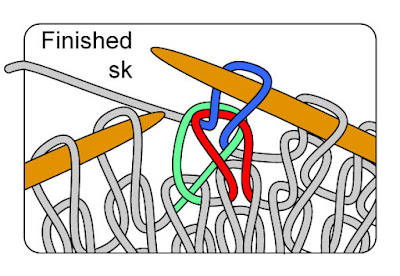

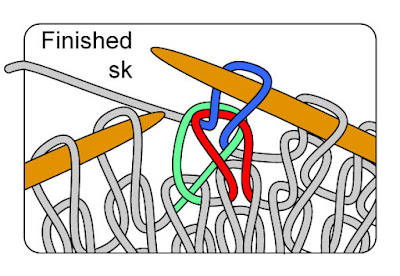

Slip, Knit (sk) In this variation on slip, slip, knit, only the first stitch is slipped knitwise to the right needle and then returned to the left needle (illustration 1, below)

The second stitch in sk remains on the left needle and is knitted together with the slipped and re-slipped stitch from its original position (illustration 2, below).

The finished sk adds a half-twist to the second (green) stitch, and so removes some of the slack from the top (red) stitch. It is also faster than ssk, as it takes fewer movements. This makes it something of an improvement over ssk, but, at least in my hands, sk remains far from a perfect match for k2tog. Further, even if you liked sk, it'd be easier to do runner up decrease #2, the 1-step sk.

* * *

RUNNER UP DECREASE #4:

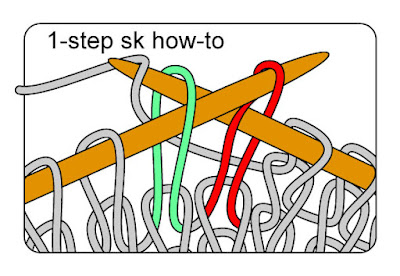

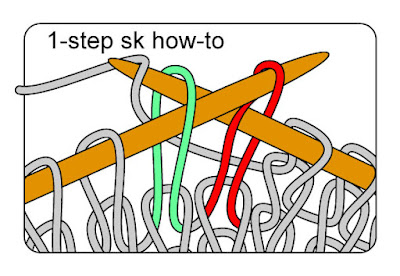

One-step sk. This is an improvement over runner up #5, regular (two-step) sk, because, as you can see, the finished product for 2-step sk and 1-step sk are identical, but the one step variation is quicker.

One-step sk is so nifty and time-saving that it was my steady date for a long time, we went through many great times together. Yet ultimately, I had to move on. Sadly, over time, I was forced to acknowledge that the result of sk (one- or two-step) is pretty much the same as ssk--too much stretching of the top (red) stitch leaves it loose and sloppy on the fabric surface.

* * *

RUNNER UP DECREASE #3:

Changing the orientation of the stitches in the row below at the time those stitches are created. In this variation, the stitches to be worked together in the decrease column (the green stitch and the red stitch) are knitted so as to change their orientation on the face of the work--in other words, they are knitted so that AT THE TIME OF CREATION, they lay LEFT arm forward, not right arm forward, and makes them already oriented for ssk. Stated yet otherwise, creating the green stitch and the red stitch to lie left-arm forward means there is no reason to do the slip knitwise, slip knitwise part of ssk--the green and red stitches are CREATED to lay the "slipped" way, ready for the final knit with no further steps to be taken at the time of decrease.

As to how the change in orientation is made at the time of creation, this depends on whether the work is circular or flat. If circular, the stitches to be decreased (the green and the red) are oriented left arm forward when knitting on the face of the fabric. This is done by means of wrapping the standing yarn

"over the top," when knitting these two stitches, a mode of yarn wrapping usually labeled "wrong." For flat knitting, the change of orientation is made on the back while purling by means of wrapping the yarn

"around the bottom," again, a mode of yarn wrapping usually labeled "wrong." The stitch which does the joining--the blue stitch--may also be oriented left arm forward; this is done by wrapping the standing yarn as shown, before knitting this stitch (i.e. wrapping "over the top")

Thinking logically, orienting the stitches to be knit together so they lay left arm forward at the time of their creation would mean there is *NO MANIPULATION* necessary, no "slip, slip." This is a potentially wonderful boon. And, for some knitters, this solution does work--a good and pleasant outcome. My knitting philosophy is: "Do what works for you." There are various successful ways to knit and we are not martinets. I will share with you, however, that I have never been notably successful with this technique--for me, the creation of stitches which cause a couple of changes of orientation within the row ruffles the fabric face in a distracting manner. If you are interested further, there is a great deal more about why I believe this is so

here.

(I have put this discussion on a "click through" page instead of in the main blog because experience shows that an eager minority of knitters--you know who you are!--can be passionate about change-of-orientation issues. For these readers--a whole separate page awaits.)* * *

RUNNER UP DECREASE #2:

Re-arranging the order of the stitches on the back.

Step 1, below: Slip the first purl (red) stitch to a stitch holder (here, a bobby pin) and hold it on the side of the fabric towards you

Step 2, below: Slip the next purl stitch to the right needle purlwise (right arm forward). Replace the first stitch onto the left needle, right arm forward, then return the second stitch to the left needle by slipping it back from the right needle. This re-arranges the stitches--puts then in different order than they started off.

As you can see, the green stitch, which will lie on the fabric surface, crosses in front of the red stitch.

Step 3, below: Give the red stitch (the one which will stay on the back of the fabric) a mighty yank. This draws the slack away from the top stitch (green) on the fabric face. insert the right needle into these two stitches in the usual manner for purling. Next, insert the right needle in the usual manner for purling.

Step 4 (below): Purl the red and green stitches together for the finished product.

I think this method of re-arranging the stitches from the back is an improvement over ssk. The manipulation mainly takes place with the red stitch which will wind up behind. This draws slack yarn away from the face of the fabric for a tidier top (green) stitch, especially once you add the "mighty yank" step to the red stitch.

However, it two disadvantages which I find offputting. First, it must be worked from the wrong side--the purl side. In stockinette, at least, this means a stitch holder, for it is far more difficult to be sure of one's place in the wilderness of purl bumps on the back than on the smooth front where decreases show. Yet, even the thinnest stitch marker leaves a trace, for at least some extra yarn must be used to "bridge over" the marker. Adding extra slack where too much slack already accumulates doesn't strike me as a good idea. Second, working with a stitch holder slows down the work. I do admit that in practice, the holder is probably not necessary unless the yarn is ultra-slippery. After all, a single stitch temporarily taken off the needles will not go far. Yet, re-capturing a loose stitch is annoying in its own right, and the more so in splitty yarn (superwash, silk, cotton, alpaca...).

Despite these disadvantages, however, you might want to put this one in your memory bank for the rare occasion when you are to make a leftward decrease on EVERY row, and you are working a flat piece of knitting. The reason? This from-the-back method is a perfect match (when viewed from the front) for ssk and a pretty good match for SYTK. Stated otherwise, there will be little noticeable variation between decreases done from the front by ssk or SYTK, and decreases made from the back by this method.

* * *

RUNNER UP #1: Re-arranging the order of the stitches on the front of the fabric at the time of making the decrease (they don't stay disordered--they end up just like ssk, only tidier). This solution to the ssk problem works for the same reason re-arranging from the back works: the second stitch (the one behind--the green one) is manipulated more than the one in front (red) which pulls slack yarn away so the top (red) stitch lies neater and tidier than an ordinary ssk. Just as in the method of re-arranging from the back, in this method, too, it is best to give the stitch behind (green) a big yank, to transfer even more excess yarn to the back of the fabric.

Despite the real improvement this method displays over an ordinary ssk, this still isn't my fave--it involves a holder (or it involves re-capturing a loose stitch) and (to me--your mileage may vary) doesn't look as good as SYTK. The sequence is identical to that for re-arranging from the back side, the only difference being you do it from the front (and likely do not need a marker to show where the line of decrease is).

As you scan over these pictures, it will, of course, occur to you that you could easily twist the green stitch, thus conferring some of the advantages of SYTK on this method too, but if you're going to do that, why not just go with SYTK in the first place?

* * *

This list of alternate left-leaning decreases is by no means exhaustive. My fellow-blogger

Nona (she of the

side-to-side socks) offers a beautifully photographed series in which she experiments with

7 types of left leaning decreases.

(Nona's been MIA since late August--say you're coming back, Nona!) And even MORE decreases exist: some even appear in the comments to previous posts in this very series--and many THANKS are due those who posted

their own personal faves.

If you've gotten to the bottom of this post--if you're still standing after all this verbiage about left-leaning decreases, then you deserve an award. (The knitting-needle cluster is bonus for those who also went to the click-through page about change of orientation.) Congratulations! You are one of the few...the proud--the uber geek techno-weenies of knitting!

And, hey, while we're speaking of uber-geek -techno-weenies, a BIG thank-you goes out to Persnickety Knitter who sent an e-mail correcting a typo in runner up number 2 (the typo has been now been fixed). *Thanks* Persnickety!

--TECHknitter

You have been reading TECHknitting on "5 alternative left leaning decreases"

Today's post reviews different kinds of knitted fabrics--ribbing, garter stitch, seed stitch, moss stitch-- which are adapted to life on the edge. These stitch patterns won't curl up when unsupported along one or more edges.

Today's post reviews different kinds of knitted fabrics--ribbing, garter stitch, seed stitch, moss stitch-- which are adapted to life on the edge. These stitch patterns won't curl up when unsupported along one or more edges.