* * *

This post tackles the three most basic crochet stitches: chain stitch (ch. st), slip stitch (sl. st) and single crochet (sc). All of these are of good use to knitters for edgings, drawstrings, fabric stabilization, seaming, attaching patch pockets and so on. If this subject interests you, sit tight, we're going for a ride--it's a long post with lots of illustrations.

Crocheted chain (chain stitch, abbreviated as "ch. st.")

|

| What a crocheted chain looks like, as seen from the front |

Chains traditionally begin with a slip knot. The easiest way to form one is to create a pretzel of yarn by lifting the ball end of the yarn over the tail end forming a loop, then draw the ball end under the entire loop just made, leaving the whole assembly very soft and loose, as shown below. Next, insert the crochet hook into the pretzel from upper R to lower L, so only the inner right leg of the pretzel is over the barrel of the hook.

|

| set up to make a slip knot |

Next, hold the yarn ends in one hand and the crochet hook in the other, then pull in opposite directions. The left loop of the pretzel will snug up into a granny-knot made out of the tail end, and this knot will freely slide up and down the ball end of the yarn--voilà: a knot which slips, a slip-knot. Leave the loop of the slip knot over the barrel of the hook.

|

| finished slip knot over the barrel of the hook |

Once you have a slip knot on your hook, trap the nub of the knot between your left thumb and left middle finger, then use your left forefinger to tension the running yarn in position above the loop (running yarn=yarn running out of the ball, ball end of the yarn) as shown below. Holding the hook in your right hand, reach up and grab the running yarn from UNDERNEATH, so that the running yarn winds around the crochet hook in the clockwise direction. With the lip of the hook facing you, slide the hook down along the running yarn until the lip of the hook is over the running yarn, then draw the loaded hook down, out of the slip knit, in the direction of the arrow, as shown.

|

| set up to make the first chain |

You will now find that the yarn you drew down out of the first loop has formed a new, second loop around your hook, as shown below.

|

| first chain stitch made |

Repeat the same yarn-winding action again and you will find a new loop is created each time you draw the hook through the loop. This creates a chain of stitches--the chain stitch, shown below. Note that when just about to work the chain stitch, there are two yarns over the hook: the just-made loop through which the hook is inserted (arrow #1) while the running yarn caught under the lip of the hook waiting to be drawn through (arrow #2) creates a second yarn over the hook-barrel.

|

| crocheted chain closeup |

The chain shown here is very loose. In real life, however, you would snug up the loops as you make them, just as you would tension your yarn in knitting.

Slip stitch (sl.st.)

For knitters, chain stitch is handy for making cords. However, its first cousin, slip stitch is much more versatile: imho it's the most useful crochet stitch a knitter can know. So useful and fundamental in fact, that even knitters who never held a crochet hook have almost certainly done the slip stitch. You see, structurally, the crocheted slip stitch is identical to the chain bind off. Yes, despite slip stitch being done with a hook and the chain bind off with knitting needle, they are the same exact stitch.The slip stitch in crocheting differs from chain stitch in only one regard. Whereas the chain is free-standing, slip stitch is worked attached to a previously created fabric. Like the chain stitch, slip stitch confers no particular height to the work. For height, more complicated crochet stitches such as single crochet, double crochet etc. must be used. Stated otherwise, although it is attached to a previously-made fabric, slip stitch more in the nature of a utility stitch: useful as an edging, fastening, or stabilizer.

Slip stitch always starts with a loop over the hook. In the illustration below, slip stitch is being made in a traditional manner: on a foundation row of chain stitch, and the existing loop comes from the last stitch of the previously-made chain (arrow #1). The hook is then inserted from front to back under the arm of the second chain from the end (arrow #2). Once you have these two yarns laying over over the barrel of the crochet hook, use the hook to catch the running yarn "up from under," so it lays as shown below (arrow #3).

| |

|

|

| first slip stitch made, set up for second one |

|

| slip stitch closeup |

|

| knitted chain bind off, closeup |

Another common use for slip stitch is to stabilize a crocheted chain. When you slip stitch into a chain as shown in the slip stitch closeup, you get a double-sided, double thick chain (a good trick to thicken and strengthen a chain-stitch for high-use drawstrings).

Slip stitch can stabilize knit fabric, too. When used on knit fabric, slip stitch does not required a foundation row. In other words, no need to make a chain, just start right in slip stitching through the knit fabric. Below is a closeup of the slip stitch through the middle of a fabric--in this case, used to stabilize the neckline of a garment which would otherwise sag.

|

| slip stitching through knit fabric to stabilize a sweater neck |

When working the slip stitch through the middle of a fabric, begin by deciding on which fabric face of the garment you want the pretty-looking "chained" part of the slip stitch to appear. We'll call this fabric face the "front," because it will be facing you when working the slip stitch. Note, however, that sometimes the pretty side might be what you normally think of as the back or inside fabric face of the garment.

In the example above, the fabric being stabilized is the back of a stockinette sweater with a fold-over collar. The outside of the neck is hidden under the collar, so the purled fabric inside of the sweater neck (which you might see at certain angles if the sweater is worn unbuttoned) is the pretty ("front") fabric face in this example.

To start the slip stitching, hold the yarn on the not-pretty side--the back side. Insert the hook from the front to the back and draw up a loop. Keeping the loop over the barrel of the hook, move the hook one stitch over, then insert the hook through the fabric again and draw up a second loop from the back. Finish the slip stitch by drawing this second loop through the first. For each slip stitch wanted, repeat the process. Finish by cutting the running yarn then pull the resulting tail through the last loop. Work this tail in as you would for a cut-end in knitting--skim it in (with a sewing needle or with a knit-picker on the fabric-back, or weave it in).

Slip stitch can also be used to stabilize the long edge of a fabric. Because there is already a TECHknitting post on this, the instructions are not repeated here, but here's a photo to show the idea. (Both the post and the below photo show a stabilizing slip stitch on a garter stitch edge--the long edge of garter stitch is especially prone to flaring--but slip stitching can be worked through any sort of knit fabric.)

|

| slip stitching to stabilize a garter stitch edge* |

Yet another common use for slip stitch is in seaming, to attach two pieces of knitting together. This is done exactly the same as slip stitching to stabilize a long edge, the only difference being that you would hold the two pieces of knitting one behind the other and slip stitch through both at the same time, matching stitch for stitch. The below schematic shows the idea, however, you must decide for yourself which column edge to work along: the schematic shows the hook inserted 1/2 column in from the edge, yet a loose fabric might require an entire column.

When used for seaming, slip stitch can be easily removed if you find you've gotten off your stitch-for-stitch count, or if you find your tension is wrong. This is a huge advantage over picking out sewing, especially easier than picking out mattress stitch. On the downside, a slip-stitched seam is bulkier than a sewn one, yet even this disadvantage can be minimized by working the seam in a color-matched thin (sock) yarn, instead of the bulkier main garment yarn.

Attaching patch pockets on sweater fronts is another great use of slip stitch. Worked vertically, the "knit column" look of the slip stitch makes this blend right in, worked horizontally, the slip stitch looks like a particularly lovely stitch pick up and bind off.

Eliminating gaps on cables is a good trick too. You know that gap that forms behind a giant cable where the cable arms twist over one another? A line of discreet slip stitching right between the arms of the outermost cable columns will seal that gap forever. The stitching will show on the inside, sure, but on the outside the addition of an extra column will never show, the little V's of the slip stitch simply disappear amongst the stockinette columns of the cables themselves. Here's a link to a project on Ravelry which shows this trick used to close the gaps on a super-wide cable. (Link used by permission, thanks to Raveler HelloKnitty6).

Single-crochet (sc)

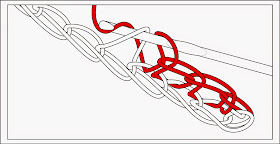

In terms of progression and complication, slip stitch was "chain stitch plus:" chain stitch + attachment to fabric edge = slip stitch. In this same way, single crochet is "slip stitch plus." This time, the extra step involves making an extra loop with the hook before the final draw through: slip stitch + extra loop = single crochet. This extra loop adds height to the stitch. So, unlike (the very flat) slip stitch, it is perfectly possible to make a fabric in single crochet.Like slip stitch, single crochet traditionally begins on a chain foundation row. So, if this illustration looks familiar, that's because it's the exact same set up as for the slip stitch. However, this time, instead of pulling the running yarn (gray) through BOTH loops on the needle as for slip stitch, STOP when you've pulled the running yarn through only the FIRST loop, as shown below.

The loop just made (gray) is over the barrel of the hook. Reload the hook: wrap the running yarn (which I've now colored red) around the barrel of the hook, slide the hook down along the running yarn until the running yarn is caught under the hook lip. There will again be three yarns over the needle as shown below--the now-red running yarn, the gray loop previously made, and last on the needle, the loop from the original chain. Draw the red running yarn through both loops, in the direction of the blue arrow to make the first sc.

|

| step 2 of the sc |

The result (first finished sc) is as below.

.jpg) |

| first finished sc, worked on a chain stitch foundation |

The cycle begins again by inserting the hook under the arm of the next foundation stitch and pulling a single loop through the arm only.

Work a several sc's and the structure becomes apparent--the top (red) loop looks just like a slip stitch (or a chain bind off, since those are the same thing) but the blue bar highlights the additional layer of (gray) loops. These are the "extra step" loops--one per stitch--which make single crochet a taller (higher) fabric than slip stitch.

|

| single crochet on a chain stitch foundation, closeup |

Knitters commonly use single crochet as an edging on baby blankets, scarves and the like. Below is a close-up of the look.

|

| sc border worked on knitted (garter st) fabric |

For this use, no need to have a foundation chain. In other words, just as slip stitch can be worked directly through a knit fabric, so too with single crochet edging. Begin by pulling the first loop through the knit fabric from back to front. * Retaining the loop on the hook, insert the hook into the next knit stitch and pull up a second loop. On these two loops, work the single crochet as shown above, second-to-last illustration. Repeat from * all the way around the blanket. A very neat finish can be worked the same way you'd bind off circular knits (the first method at the link would be the best one to use for sc).

Addendum: If you want to know more about crocheting, here is a website (Annie's Craft Store) with sensational crochet illustrations--I admire the illustrations greatly, they are clear and beautiful.

Until the next post, good knitting (or should I say, crocheting?)

--TK

* The two photos with the asterisks (seam and stabilization photos) come from a TECHknitting Ravelry pattern for the Elizabeth Cap-- the slip stitch seam and edging help stabilize the cap's very stretchy garter stitch fabric. If you go to the link, you'll see it works: some of caps shown with the pattern at the link had been regularly worn by the time they were photographed, but the slip stitching prevented stretching or sagging and kept them looking new.

This has been aTECHknitting blog post about crocheting for knitters, featuring chain stitch (ch. st.) slip stitch (sl st) and single crochet (sc). Thanks for reading!